“Cultural citizenship, like all other forms of citizenship, is constituted by a process of continuous performance rather than a set of abstract legal rules” (Stevenson, 2003).

Eurovision is the international live music epicenter. It’s one of, or if not the world’s largest singing competition. Since 1965, member countries from the European Broadcasting Union have come together in pockets of Europe to compete on the world stage. Somehow, Australia is also included (ABC is in the EBU). Now, the Eurovision ‘spectacle’ draws over 100 million viewers each year.

In Eurovision, a country’s cultural identity and how it is showcased through song is a country’s strong suit. Member countries get to put forth national ideas and represent themselves with these ideas throughout the duration of the competition. What is imagined to be a collaborative and spectacular display of nationhood inside celebrational performances of cultural differences – can be looked at differently when we talk about Russia’s involvement in Eurovision. It’s hard to have a universally accepted idea of gay pride and celebrate that idea (without issue) in Eurovision if some countries condemn the show as “homosexual propaganda.” In 2014, St Petersburgh lawmaker, Vitaly Milonov stated that Russian performers’ participation would “contradict the path of cultural and moral renewal that Russia stands on today”, also calling for a boycott of the “sodom” show.

Eurovision teaches us that the spread of ideologies across borders is a continuous performance of all countries involved. Countries stand for what they believe in, and sometimes make subtle political comment (although they are banned). Some countries do not accept ideas that other countries condone, for example, homosexuality is widely accepted throughout Europe, but Russia actively protests against it. There is a division of law and societal opinion/cultural ideas between countries, and countries vary in their national ethos. Eurovision is politically charged and in its production, can be in conflict and compromise with differing cultural ideas. Eurovision and it’s competing countries prove more complex, and not always harmonious.

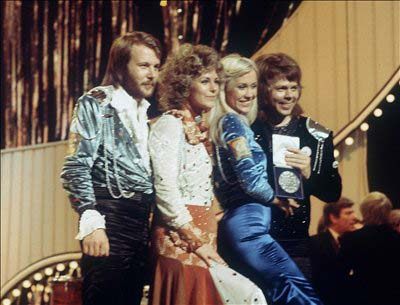

What can Eurovision teach us about the spread of ideologies across borders? The short answer is ABBA. And all that ABBA is. Honestly, Eurovision winners today have nothing on the Swedish sensation. And their fabulous hippie pants. Because of ABBA (winning Eurovision and becoming the world’s biggest band), the spread of ideologies across borders has allowed for the globalisation of Swedish popular music. It was only after ABBA that Swedish artists succeeded at an international level. In the time after ABBA won Eurovision, a frenzy of songwriters and popstars flew to Sweden just to get the chance to collaborate with ABBA’s producers. They wanted the sound that only Swedish pop music bred in the 1970’s. Quirky, new dance-pop and untraditional pop instrumentation quickly took over the global music scene. (Johannson, 2010)

https://craighill.net/2012/04/06/april-6-1974-abba-wins-eurovision-contest/

When Brexit happened, the world collectively went: OMG! England can’t leave Eurovision! Theatre kids wept across the globe, and they were not stressing for the European Union, nay, but what would happen to the English ballads if the Brits were banished from singing songs on Eurovision?!? Well, ‘Eurovision Brexit’ produced more than half a million search results which fans ate up. There was hustle and bustle and a commotion of speculation, until fans were assured that England could compete while the BBC is still a part of the EBU (European Broadcasting Union). What ‘Eurovision Brexit’ searches teach us about the spread of ideologies across borders, is that information on the internet, especially when intertwined in dedicated fanbases; travels incredibly fast.

References:

Bomsdorf, C., 2014. Bearded Lady from Austria Ignites Eurovision Protest Storm. Image. [online] WSJ. Available at: <https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-RTBB-4316>.

Hill, C., 2012. April 6 1974 ABBA Wins Eurovision Contest. Image. [online] Craig Hill. Available at: <https://craighill.net/2012/04/06/april-6-1974-abba-wins-eurovision-contest/>.

Johansson, O., 2010. Beyond ABBA: The Globalization of Swedish Popular Music. Focus on Geography, [online] 53(4), pp.134-141. Available at: <https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1949-8535.2010.00016.x>.

Luhn, A., 2014. Russian politician condemns Eurovision as ‘Europe-wide gay parade’. [online] The Guardian. Available at: <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/apr/30/russia-boycott-eurovision-gay-parade>.

Middlemost, R., 2021. BCM 289 Week 3: Eurovision.

Pew Research Center’s Global Attitudes Project. 2013. The Global Divide on Homosexuality. [online] Available at: <https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2013/06/04/the-global-divide-on-homosexuality/>.

Robinson, F., 2017. 13 times Eurovision got super political. [online] POLITICO. Available at: <https://www.politico.eu/article/13-times-eurovision-song-contest-got-political/>.

Sivasubramanian, S., 2016. What does Brexit mean for Eurovision?. [online] SBS. Available at: <https://www.sbs.com.au/programs/eurovision/article/2016/06/27/what-does-brexit-mean-eurovision>.

Stevenson, N., 2003. Cultural Citizenship in the ‘Cultural’ Society: A Cosmopolitan Approach. Citizenship Studies, [online] 7(3), pp.331-348. Available at: <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240528647_Cultural_Citizenship_in_the_’Cultural’_Society_A_Cosmopolitan_Approach>.